The Designated Devil: Why Some Families Needs One

There is an unacknowledged, unlit, but oh-so-necessary role that exists in some families. Someone who carries the invisible ledger. Not the sibling whose voice dominates every room. No, of course not the one who commands attention with charm or anger. Not the black sheep, who fails visibly and can be explained. Not the rebel, whose departure makes a kind of narrative sense. This is someone quieter. Someone whose presence is both indispensable and unremarkable.

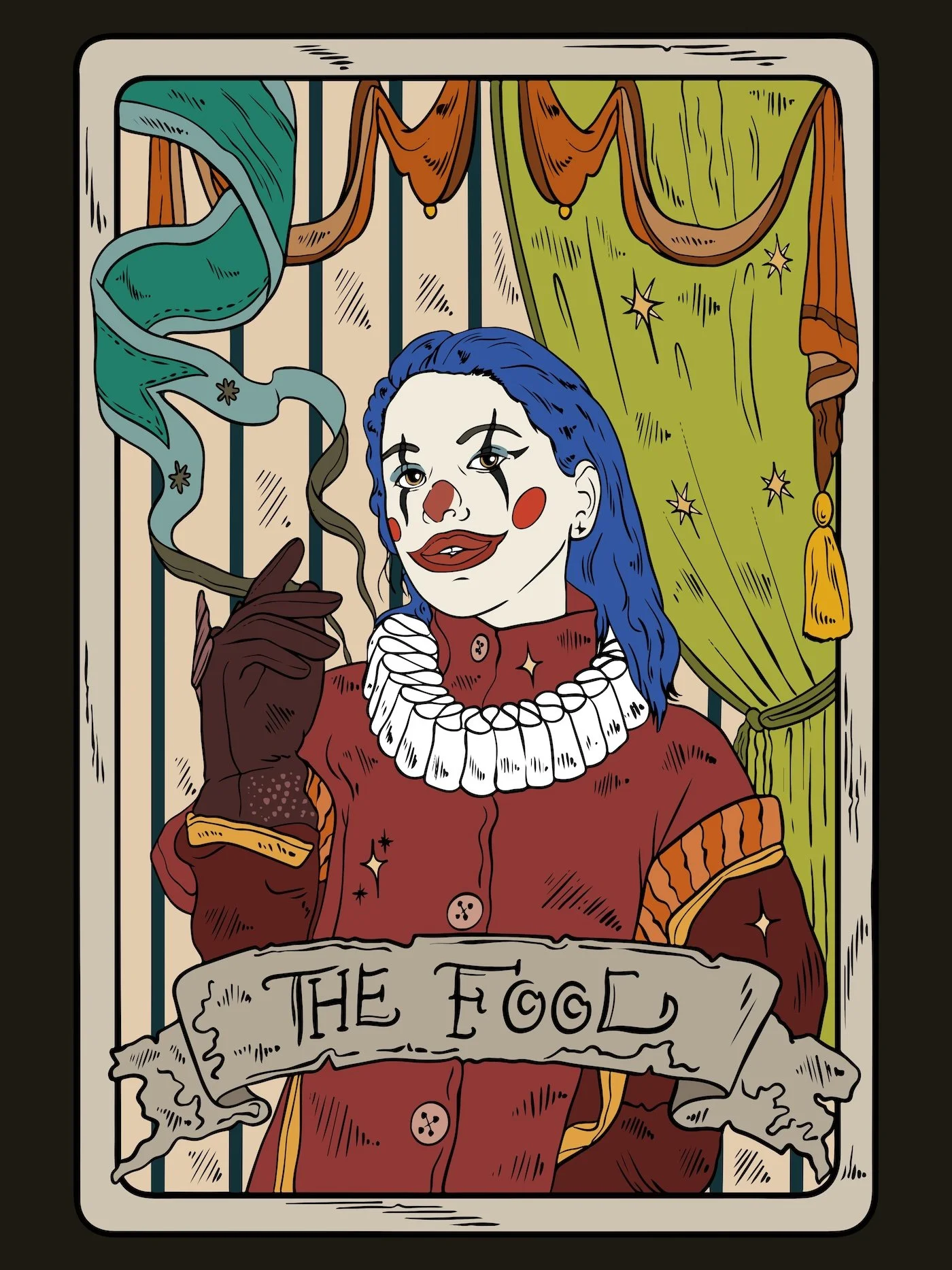

This is the designated devil. The one who carries what the family cannot metabolise. The one whose memory is the problem. The one who by continuing to exist, to remember, to decline the invitation to collective amnesia; threatens the story the family tells itself in order to remain a family.

Every system needs a place to put its contradictions. In families, that place is usually a person.

The role exists in abundance. You may not notice it, because its survival depends on discretion. The designated devil speaks softly or not at all, measures every word, every glance, every gesture, and navigates the room like a delicate algorithm of avoidance and observation. They carry histories the group cannot name, emotions the system cannot contain, and, often, truths that would destabilise if spoken aloud. Their labour is invisible precisely because it must be. And yet, without it, the machinery of intimacy, organisation, or hierarchy grinds unevenly, creaking, threatening collapse.

René Girard called it the scapegoat mechanism: societies, he observed, maintain coherence by channeling conflict and tension into a single body. Family systems theory echoes this insight. Bowen’s “identified patient” becomes the locus for dysfunction that no one else can tolerate. The designated devil is both central and peripheral, necessary and expendable, watched and unobserved.

The remarkable thing, Girard observed, is that the community genuinely believes in the scapegoat's guilt. The violence done to this person is not experienced as violence. It is experienced as restoration. As hygiene. As the return of peace. The family is simply the smallest unit in which this mechanism operates. The dining table as sacrificial altar. The holiday gathering as ritual expulsion. And someone is learning to say fine the way others learn to breathe.

We exist aplenty, we designated devils. In therapy waiting rooms and in the poker-faced silences of family gatherings. In the measured half-sentences and the strategic vagueness and the art, honed over decades, of conveying nothing while appearing to participate. We recognise each other not by what we say but by the architecture of what we withhold - those load-bearing walls of unspeakable knowledge, the sealed rooms where memory is kept.

But we are quiet. And our quietness has a shape. A cost. A meaning that extends far beyond the families that taught us silence was survival.

On Silence

Noise invites attention. Articulation is risky. Speaking too loudly may undo the tenuous equilibrium the devil maintains. And perhaps also, since the world (from childhood to corporate boardroom) has no vocabulary for gratitude toward the invisible labourer. Silence becomes both armour and language.

There is a certain power in this quietude, a form of knowledge that comes from unrelenting observation and survival. Societies, institutions, and families persist in part because someone quietly absorbs the friction, the contradiction, the unspoken rule, the unwept grief. And in that silence, the designated devil sees the fissures others ignore, remembers the details that others rewrite, calculates outcomes that no one else can.

She learns early that precision is dangerous through years of watching a careful sentence be dismantled before it reaches its end. She learns to abandon thoughts mid-formation. To swallow the part that might land. To replace this happened with I might be misremembering. She learns the alchemy of trading memory for tone, accuracy for peace, the thing she knows for the thing that will let her stay in the room.

Virginia Woolf wrote of the Angel in the House - that phantom of Victorian femininity who whispered to women writers, Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles. The designated devil has her own angel, her own phantom. It whispers: Be smooth. Be vague. Be a stone with no handles. Give them nothing to grip.

And this is the masterstroke - she learns that defending herself only proves the accusation. The devil would protest, wouldn't she. The difficult one would have a rebuttal. The airtight logic of the role: to speak is to confirm, to stay silent is to accept. There is no door marked exit.

So she stops explaining. Not from defeat exactly - no, rather, from mathematics. She has run the calculations enough times to know: the variable was never her behaviour.

Consider the civil servant who records data no one wants to confront, the archivist who preserves inconvenient histories, the human-rights worker who bears witness to atrocities others forget. The mechanisms are the same: the system cannot tolerate all truths, so someone must hold them. The world persists not because injustice disappears, but because someone keeps tally, silently, faithfully, without reward.

There is a paradox here: the same qualities that render the designated devil indispensable - observation, memory, insight, restraint - are often invisible, misunderstood, or condemned. The world rewards the loud, the visible, the charismatic, but it is the quiet who map the fissures, navigate them, and ensure continuity. And the truth is, many of us are designated devils in one form or another — in our families, our workplaces, our social networks. We are the ones who watch when others look away, who carry what cannot be spoken, who calibrate, predict, and absorb.

To exist in this role is to develop a rare acuity, a deep understanding of human systems, a persistent awareness of shadow and light. Yet the role also exacts a toll. It asks us to measure ourselves against expectations we cannot name, to negotiate our presence in ways that leave no trace, to act in service of systems that may never acknowledge our labour. And in that tension, there is both power and invisibility, insight and isolation, endurance and exhaustion.

What the Body Knows

Psychologist Stephen Porges describes something he calls “neuroception” - the way our autonomic nervous system reads the environment for safety or danger before conscious thought can intervene. We are always, in every moment, calculating threat at a level below language.

In certain families, the neuroception never rests. The body stays on. Low hum, constant readiness. So familiar it becomes nothing. Just baseline. Just how life is. The muscles know before the mind does. The jaw, the shoulders, the space between the vertebrae where decades of swallowed sentences are stored.

Bessel van der Kolk writes that the body keeps the score. Of all the times you knew something and said fine instead. The score is kept in tissue, in posture, in the way the throat closes before certain words. Not pain exactly. A bracing. A readiness that feels like rest until someone touches you gently and you flinch.

The designated devil is a diplomat without a country. She can read a room's weather from the doorway. The barometric pressure of mood, the chance of sudden storms. This is sometimes called sensitivity. Sometimes emotional intelligence. It is also, always, the residue of necessity. The skill you develop when not-noticing is not an option.

What We Lose

Here is what I keep thinking about: the designated devil is usually the one who saw something.

Her crime (the original crime, the one that got her cast) was not cruelty or failure or even rebellion. It was witnessing. She was in the room. She remembers what was said. She noticed the distance between the family's narrative and the family's actions, and she made the error of not forgetting.

This is her utility and her danger. She holds the archive the family needs destroyed.

Scale this up. Past the dining table, past the childhood bedroom with its silence. Into workplaces, institutions, communities, countries. The scapegoat mechanism does not require blood relation. It requires only a group with a story to protect and a person inconvenient to that story. T

he whistleblower who becomes disgruntled. The employee whose questions are reclassified as attitude problems. The one who won't pretend the emperor's clothes are visible. We lose these people. Sometimes they simply go quiet. They learn the calculation. They stop raising their hands. They do their work and keep their observations filed away in the sealed rooms of the self, because they have learned, in the body, what happens to those who unseal them.

This is not only personal loss, though it is that. The designated devil has been watching from the kitchen door her whole life. She knows what goes into every dish. She knows the ingredients shown to guests, the ones hidden, the substitutions made when no one was looking.

On Hope as Wound

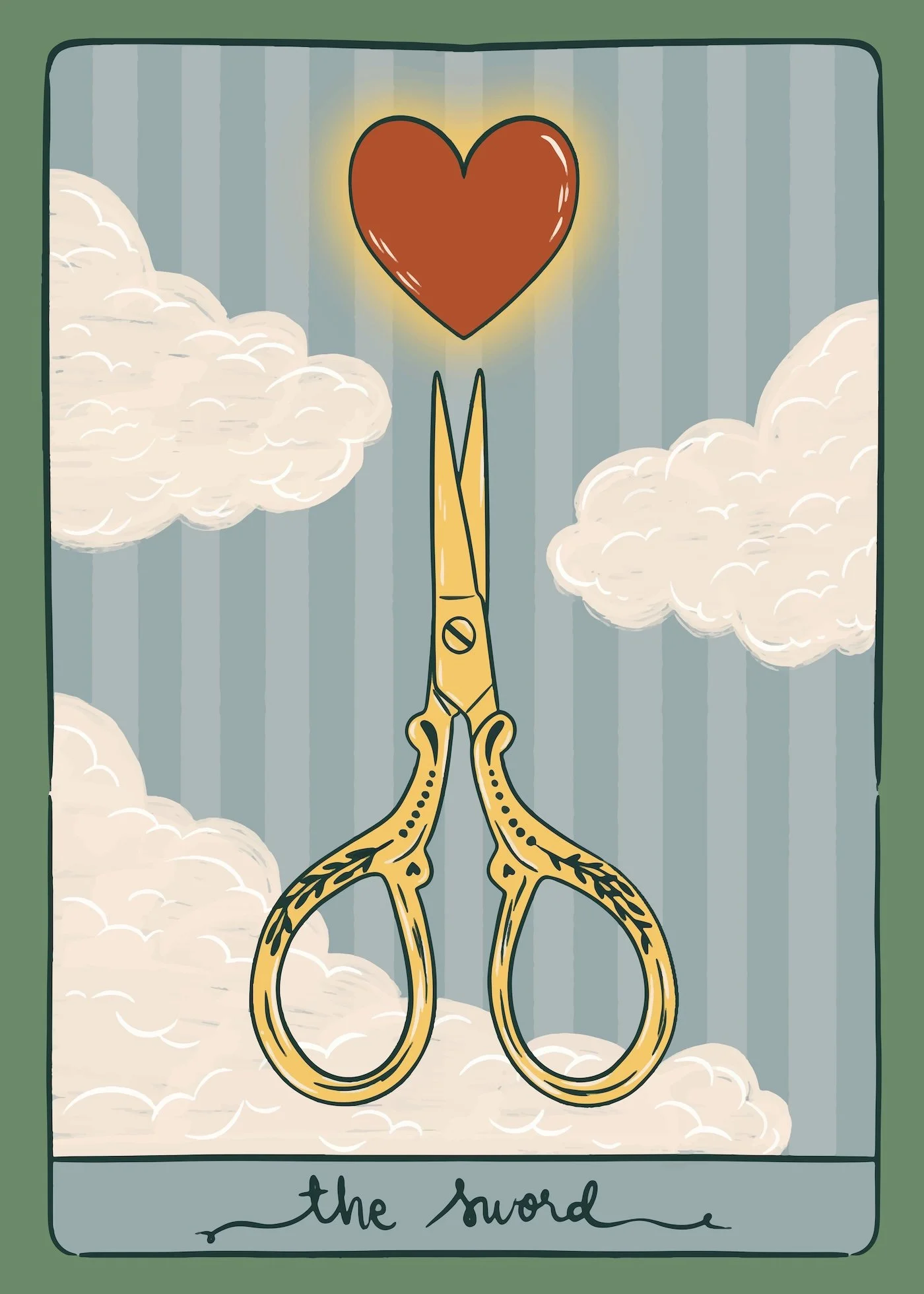

The designated devil's flaw (if we must call it a flaw) is not her memory, though that is what they punish. It is her hope. Her persistent, foolish, animal hope that this time might be different. That the explanation she offers might land. That the relationship might be repairable. That people can change, because she has changed, because she has done the work, and she cannot quite believe others haven't done the same.

She returns to the table. She extends the olive branch. She offers forgiveness for things that were done to her, accepts it for things she did not do. She agrees to terms she is not told until she has violated them.

This is not weakness, though it is often named as such. It is something more like faith. Faith in the possibility of redemption, of recognition, of the story being revised in the direction of truth. The designated devil is, despite everything, a romantic. She believes in the conversion narrative. She keeps waiting for the family to see her clearly, the way a child waits for a parent who is not coming home.

The hope is the wound. The willingness is the wound. The soft tissue through which the knife slides easiest.

What Might Change

Girard thought the scapegoat mechanism was foundational. That groups cohere by expelling, that community is built on the bodies of the excluded. To interrupt it would require a kind of collective awakening, a recognition of the mechanism as it operates.

But perhaps something smaller?

Notice who has gone quiet. Ask what it might cost them to speak. Stay curious one beat longer than comfort allows. Consider that the difficult person might be difficult because they are holding what the group refuses to carry. That the family's warmth might be purchased with someone else's silence.

The designated devil is not asking to be believed automatically. She is not asking to be centered, celebrated, restored to some imagined rightful place. She is asking only this: that the room admit she might be seeing something real. That her memory be treated as data rather than distortion. That the story be willing to include a chapter it has worked very hard to tear out. She knows the difference between what is served and what is true. The question is whether the rest of us are hungry enough to want to know.

If we could truly see the designated devils among us - acknowledge their quiet work - what might we learn? About empathy, about resilience, about the structures we inhabit? Perhaps we would begin to notice the subtle currents that sustain families, organisations, and societies. Perhaps we would finally understand how much of what appears orderly, just, or inevitable depends on those who quietly hold the weight.

She will say fine. She has been saying it for years. The smooth stone, the coin that keeps the transaction moving, the word with no handles. But sometimes fine is not compliance. Sometimes it is the quietest form of resistance. The refusal to perform an okayness she does not feel. The decision to stop explaining her meal to people who were never hungry.

Fine, fine, fine. And underneath it, still breathing: the memory that would not be erased. The witness who did not look away. The devil says fine.